Walking into the Rubin Museum just off of 17th Street in the Chelsea neighborhood, a sense of tranquility washes over you. The dark wood floors juxtaposed against the large windows inviting light to flood in creates a comforting environment, which is much appreciated in a city as chaotic as New York.

The Rubin Museum was established by Shelley and Donald Rubin in October of 2004 when the couple purchased an old Barneys Department store, and with the help of Beyer Blinder Belle Architecture firm, remodeled the space in order to hold their private Himalayan art collection that they had been assembling since 1974. The couple began their collection when they fell in love with a pair of Tibetan paintings found in New York City. Since then, due to the fortune Donald Rubin earned over his career, the couple has assembled one of the largest Himalayan collections, dating back to the 11th century. The Rubin Museum’s Executive Director is Patrick Sears, while the Director of Exhibitions is Jan Van Alphen. In 2013, Patrick Sears made a total of $324,061, while Jan Van Alphen made $222,067. However, the total revenue for 2013 was 6,155,768, which is less than half of what they made in 2011, which was recorded as $31,179,124. As the annual revenue of the Rubin Museum has decreased, the salaries of the executive director and the director of exhibitions have neglected to reflect this.

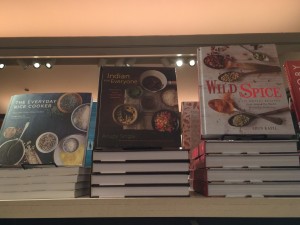

The collection of the Rubin Museum is displayed throughout seven floors, all of which is accessible by the steel and marble spiral staircase. The street level space is an open environment that connects the admissions desk, café, and gift shop.The café is spacious, yet almost cozy due to the warmth of the wood and the soft-lit lamps that hang from the ceiling. The Museum Gift Shop is tucked off to the left side of the café, facing 17th Street with huge windows. It is difficult to miss due to the array of rainbow hues and decorative ornaments that the Rubin Museum website boasts are “the finest artisanal goods from the Himalayas and across Asia—many unavailable elsewhere in the United States” (rubinmuseum.org). The large windows allow for natural light to flood the space, creating a sense of openness that counters the vast number of objects that this cozy gift shop holds. Enclosed in glass cases are necklaces, earrings, and pendants all of Himalayan style and design.These items are expensive, presumably crafted of high quality metals and stones. Necklaces range from $150- $380, while earrings are sold at around $60. Following the cases of jewelry is an extensive collection of books ranging from non-fiction narratives that take place in the Himalayan region, to religious books focused on Buddhism, to cook books specializing in South Asian spices and ancient cooking traditions. All the books are reasonably priced (most sold at around $20), and therefore attract a majority of the gift shop customers.

Enclosed in glass cases are necklaces, earrings, and pendants all of Himalayan style and design.These items are expensive, presumably crafted of high quality metals and stones. Necklaces range from $150- $380, while earrings are sold at around $60. Following the cases of jewelry is an extensive collection of books ranging from non-fiction narratives that take place in the Himalayan region, to religious books focused on Buddhism, to cook books specializing in South Asian spices and ancient cooking traditions. All the books are reasonably priced (most sold at around $20), and therefore attract a majority of the gift shop customers.

Followed by the shelves of books is a shelf entirely of decorative, embroidered pillows, which are extremely beautiful and evidently high quality. Each are sold at $275, which appears to be a steep price. However, for majority of the clients whom the Rubin museum gift shop attracts, this is a small price for such a culturally embellished item.

The gift shop also holds a vast number of kids books and toys, which all demonstrate the wide variety of Himalayan cultures that are experienced in the museum. Numerous household and kitchen items such as plates, bowls, utensils, teapots, candles, and incense — strongly exemplify the character of this culture as well.

The gift shop also holds a vast number of kids books and toys, which all demonstrate the wide variety of Himalayan cultures that are experienced in the museum. Numerous household and kitchen items such as plates, bowls, utensils, teapots, candles, and incense — strongly exemplify the character of this culture as well.

The most popular items are the scarves that vary in color and in texture. The scarves range in price from $25 to $250, the more expensive ones are placed at the very top, cascading over the mid-range priced yet equally robust in color, which flow onto the most delicate, albeit lowest priced, scarves.

By the cash register, stands hold hand-made beaded bracelets and necklaces from Nepal. These pieces of jewelry are all fair-trade, meaning they provide the women who made them with fair income and benefits in a “safe and healthy work environment.” Small cards with this information are placed close to the jewelry informing, and often encouraging the customer in the prospect of purchasing such items.

Items such as the fair trade jewelry create a sense of sense of intimacy as the customers find the value of these objects to have increased due to the connection they create between the Himalayan culture and the customers’ contribution to it. According to cultural sociologist Sharon Zukin in her book Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change (1982) an “institutional framework–the museum or the cultural center–[can] become a vehicle for its own valorization” (177). Although these particular Himalayan items are not sold as art, the museum setting itself adds value to these objects.  Although these beaded bracelets and necklaces are not considered art, because the Rubin strictly presents Himalayan culture, this setting emphasizes their authenticity and in turn increases their value to customers. This notion is extended to the higher priced items, such as the ornate masks in the gift shop that are specifically being sold due to a temporary exhibit on the art of mask traditions. Due to the high pricing on these masks, and other objects such as the embroidered pillows or high quality scarves, it is evident only those of the upper middle class or upper class can afford such items. As a result, it comes into question why such people are buying these objects they possibly have no knowledge pertaining to their cultural significance, or if they do, why are they willing to pay such a high price.

Although these beaded bracelets and necklaces are not considered art, because the Rubin strictly presents Himalayan culture, this setting emphasizes their authenticity and in turn increases their value to customers. This notion is extended to the higher priced items, such as the ornate masks in the gift shop that are specifically being sold due to a temporary exhibit on the art of mask traditions. Due to the high pricing on these masks, and other objects such as the embroidered pillows or high quality scarves, it is evident only those of the upper middle class or upper class can afford such items. As a result, it comes into question why such people are buying these objects they possibly have no knowledge pertaining to their cultural significance, or if they do, why are they willing to pay such a high price.

For many, there is an opportunity to gain cultural capital by buying such objects for, according to French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, “cultural capital objectified in material objects and media… is transmissible in its materiality” (The Forms of Capital). Bourdieu explains such objects transmissibility is rather “legal ownership and not (or not necessarily) what constitutes the precondition for specific appropriation.” Therefore, it is not necessarily a result that the customers of the Rubin gift shop are culturally appropriating such objects. Nevertheless, it is possible customers gain cultural capital from the objectification of what the Rubin Museum gift shop sells in order to “promote understanding, and inspire personal connections to the ideas, cultures, and art of the Himalayan Asia” (rubinmuseum.org).

— Geneva Smith

Sources Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (New York, Greenwood), 241-258. Online: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/fr/bourdieu-forms-capital.htm Last accessed: June 25, 2015.

Zukin, Sharon. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1982. Print.