Founded in 1968 by a group of artists, political figures, philanthropists, curators, and civic leaders who wanted to enfranchise the disenfranchised, The Studio Museum in Harlem is dedicated to cultivating emerging black creativity and exploring black aesthetics. “Committed to expanding the resources, opportunities and institutional attention pai d to black artists, the Museum’s founders wrote, ‘We have chosen Harlem as the place for this more experimental, less institutionalized Museum because of the sense of newness, strength, and change which is present there’” (Golden 2015). The Store at the Studio Museum is a fascinating site for us to consume, and refract images of blackness for education, entertainment, and communal storytelling.

d to black artists, the Museum’s founders wrote, ‘We have chosen Harlem as the place for this more experimental, less institutionalized Museum because of the sense of newness, strength, and change which is present there’” (Golden 2015). The Store at the Studio Museum is a fascinating site for us to consume, and refract images of blackness for education, entertainment, and communal storytelling.

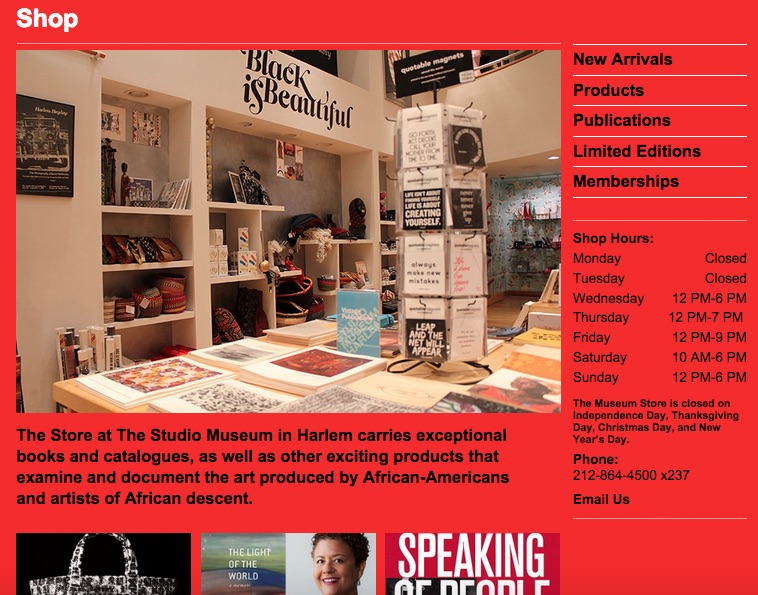

The Studio Museum in Harlem is across the street from the monolithic Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building, one block from the historic Apollo Theater to the right, with Harlem’s most delicious and expensive restaurants, Red Rooster and Sylvia’s, to the left. Smack dab between the A,B, C, D and 2,3 train stops, The Studio Museum is right at the crossroads of Harlem, “the psychic heart of black experience” (Golden 2010). Located on the ground floor of America’s first contemporary black art museum, The Store’s glass doors invite the eye in off the main drag of 125th street and greet visitors from behind the bright red Studio Museum welcome desk. The Studio Museum has 4,403 square feet of exhibition space, 2,527 square feet for public education programs, and 1,906 square feet dedicated to the gift shop. Outside, David Hammond’s green, red, and black African American Flag flies proudly, boldly, silently. Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue plays on loop, airy light filters in from the street and through the glass doors leading back to the gallery. Glenn Ligon’s light sculpture, “Give Us a Poem” pulses.

Open Wednesday through Sunday, The Store at the Studio Museum operates with a small life and entrance of its own, allowing the gift shop to function and fit the local urban landscape as another commercial outpost along 125th Street, but what is the nature of its goods for sale? And who are its buyers?

Let’s start online. First off, we notice some curious digital inconsistency. The Store’s layout has a bright red background, a schematic negative of the rest of the Studio Museum’s website which uses a white background with red and black font. What is peculiar however is that the title of the page, “The Shop”, is inconsistent with the url. Once a customer attempts to buy an item, the button redirects to Amazon, which means the site was never built to host a cart or online store function, and therefore whomever runs the site has used a hyperlink Band-Aid that does not allow the online admins to track the user behavior from browsing information about the museum’s history or current exhibitions into a completed transaction, therefore not telling the online writers how to direct the online web presence of the museum or how to edit the menu bars, color scheme, or button placement to encourage potential customers to browse and finally buy.

1. “exceptional books and catalogues”: Institutional embrace of exceptional blackness?

1. “exceptional books and catalogues”: Institutional embrace of exceptional blackness?

2. “catalogues”: The Studio Museum is in Harlem, what does the English spelling say about the Museum’s pivot towards the academic (rather than?) the local.

3. “examine and document the art” : Save the art? Protect the art? Is the art dying?

4. “African-Americans and artists of African descent”: Signals a subtle but crucial rhetorical movement away from Pan-Africanism towards multiculturalism within the Black Diaspora, which may signal a search for black aesthetic(s) and the representation of black experience.

D.L. Smith a beloved former Africana and English professor of mine at Williams College, is worth quoting here at length:

The concept of “blackness” was—and is—inherently overburdened with essentialist, ahistorical entailments. An adequate account of African-American aesthetic practices would call the concept of ‘blackness’ into question, and the failure to question this concept would inevitability lead to muddled theories…Consider the difference between “The Black Aesthetic” and “Black Aesthetics.” The former suggests a single principle, while the latter leaves open multiple possibilities. The former is closed and prescriptive; the latter, open and descriptive. The quest for one true aesthetic corresponds to the notion of an essential ‘blackness,’ a true nature to all “black” people. This is the logic of race, a logic created to perpetuate oppression and not to describe the subtle realties of actual experience. The choice of “the Black Aesthetic” rather than “Black Aesthetics” represents a fundamental theoretical failure of the Black Arts Movement…we might consider what it means to envision the African-American cultural tradition as plural, not singular.

(Smith 1991: 95-96)

Can we buy blackness?

No but we can corroborate blackness, we can pursue blackness, we can display blackness, we can buy artifacts that signal, we can amass collections that signify. Our purchasing patterns can be understood as patterns of power, in the sense that we can wield power through our appearance that may not be ours, but rather access a power in images, a power in an aesthetic, such as “Black is Beautiful”. Which is to say, “Black is worthy,” “Black is powerful,” and “be beautiful by being black”. The signature item and key statement is “Black is Beautiful”. First coined by the Jamaican born father of Pan Africanism, Marcus Garvey, the UNIA political slogan is now sold on mugs and T-shirts for $12 and $25 respectively.

Is such blackness black or colorful?

On the right side of the gift shop are domestic decorating items such as a tote bag designed by MZ Wallace and the artist Glenn Ligon’s Untitled / (I Am Somebody) for $225 where all proceeds support the Studio Museum. Amidst a panoply of hipster home goods such as wine bags, Kodak film, mustache chip clips, sarcastic greeting cards, and antique key carabineers, there was a bright yellow book that caught my eye, Remix: Decorating with Culture, Objects, and Soul. Next to it were cheetah pattern faux ivory bottle openers. Remix opens, “From Afrocentric to Aphrochic. We encourage everyone to look at design through their own cultural lens in order to decorate a home that reflects who they are. Over the past thirty years, remix has become a household word in African American music. The idea of a remix is simple: rearrange old songs by adding modern elements that give them new life. We can’t think of a better way to describe our approach to modern design” (Hays, Mason & Cline 2013:1).

Is such blackness recovered or cultivated?

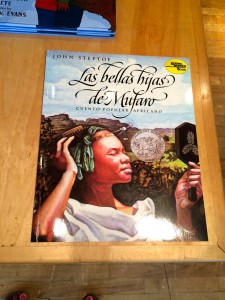

Sense of self is cultivated. The breadth of scholarly publications for sale point to a process of positioning which conscious and created with effort. One customer, a young black woman, berated the volunteers for not selling an obscure African art magazine and “supporting our brothers”. In the back right corner, rare exhibition catalogs and eight page monographs are sold for over $80. International magazines such as African Voices and NKA Journal of Contemporary African Art are on sale but the most recent copies are from 2013. On a more positive note, children’s bilingual books featuring black female characters were a refreshing sight on the wooden table marked “Young Readers”. To be spoken to, literally and figuratively, in your own language is empowering for young women of color whose first language may not be English and who are much less of a minority than American literature or media makes them out to be.

obscure African art magazine and “supporting our brothers”. In the back right corner, rare exhibition catalogs and eight page monographs are sold for over $80. International magazines such as African Voices and NKA Journal of Contemporary African Art are on sale but the most recent copies are from 2013. On a more positive note, children’s bilingual books featuring black female characters were a refreshing sight on the wooden table marked “Young Readers”. To be spoken to, literally and figuratively, in your own language is empowering for young women of color whose first language may not be English and who are much less of a minority than American literature or media makes them out to be.

If we seek to buy blackness, do we buy local or global?

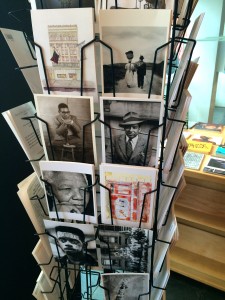

If we buy blackness we buy from each other, from the insiders. So who is inside and who is a stranger? A colonizer? A gentrifier? A phony or a fake? The price range begins at $1.50 for a Harlem postcard up to $1200 for a limited edition benefit print by a young booming, blooming artist of color including Adam Pendleton, Tanea Richardson, Saya Woolfalk, Dawit L. Petros, Leslie Hewitt, and Khalif Kelly.

While I perused the gift shop not so surreptitiously taking photographs of every inch of its displays, a Dutch couple bought the colorful woven basket from Kenya I had been eyeing. Eager to cover my own lack of capitalist intention, I approached the counter and joked I had wanted to buy the basket that was now walking out with the cheerful foreign couple. The volunteers sneered, “They always buy those.” Is bought blackness only authentic when its content is esoteric? Can we say at once, “Black is Beautiful” and insert the caveat of “when and through and according to whom?” Anthony Kwame Appiah would argue otherwise, “Cultures are made of continuities and changes, and the identity of a society can survive through these changes. Societies without change aren’t authentic; they’re just dead” (Appiah 2007:193). The Store at the Studio Museum successfully mixes continental African goods, crafts by African vendors who have relocated to America, and original pieces by local Harlem artists, but there is a notable dearth of black artists from the South or Western United States[q], only authentically New York or authentically African items. On the other hand, this is the Store at the Studio Museum in Harlem, not Blackness U.S.A. Inc. “I will be the first one to say that I still want more” (Golden 2014).

Can The Store at the Studio Museum serve as a space to exchange non-essentialized ideas of blackness packaged in an essentialized form?

Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem so, because we can’t package radical thought, wrap revolutionary representation, or tie nuance in a nice bow without losing “The Real,” which, according to Jacques Lacan, is the infinite or the powerful, and most importantly, the immaterial (Lacan 1956). “The Real” resists representation, is pre-symbol, and pre-imaginary where words fail and the truth of an experience can only be approached. Thus, representations of “blackness” and commodifications of “blackness” resist essentializating media, it informs media. If I could change one aspect of the gift shop it would be to add context to decontextualized craft items that are not directly tied to exhibitions. These decontextualized items fill the demand and canonical ideal of what visitors had perhaps expected to be in the exhibitions, such as classic Harlem photographs or wooden sculptures from Zimbabwe. Fortunately, the academic / domestic dichotomy does not carry into the exhibitions where the experiences of diverse people of color are examined carefully, compassionately, and creatively.

— Jeanelle Augustin

Works Cited

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture.

New York: Oxford UP, 1992. Print.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007. Print.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1984. Print.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone, 1994. Print.

Golden, Thelma. “Fighting Tokenism, Curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem Wants More for African-American Art.” Interview by Hilton Als. Studio360. Public Radio International, 26 Sept. 2014. Web. 15 June 2015. <http://www.studio360.org/story/thelma-golden-the-curator-is-present/>.

Golden, Thelma. “Letter from the Director.” Studio, Winter/Spring 2015 The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine (2015): 1. Print.

Hays, Jeanine, Bryan Mason, and Patrick Cline. Remix: Decorating with Culture, Objects, and Soul. Potter Style, 2013. Print.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture, the Meaning of Style. London: Methuen, 1979. Print.

Howe, Stephen. Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. London: Verso, 1998. Print.

Karp, Ivan, and Steven Lavine. Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1991. Print.

Lacan, Jacques. “Symbol and Language.”The Language of the Self. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1956. Print.

Neal, Larry. “The Black Arts Movement.” The Drama Review: TDR (Summer, 1968) MIT Press 12.4 (1968): 28-39. Print.

Smith, David Lionel. “The Black Arts Movement and Its Critics.” American Literary History, Oxford University Press 3.1 (1991): 93-110. Print.

TEDTalks: How Art Gives Shape to Cultural Change. Perf. Thelma Golden. Technology, Entertainment and Design: Ideas worth Spreading, 2010.

Vallance, Elizabeth. “Visual Culture and Art Museums: A Continuum from the Ordinary.” Visual Arts Research, University of Illinois Press 34.2 (2008): 45-54. Print.

Veblen, Thorstein, and Stuart Chase. The Theory of the Leisure Class; an Economic Study of Institutions. New York: Random House, (1934): 169-174. Print.

Vogel, Susan Mullin. “Baule: African Art Western Eyes.” Yale University Press: African Arts 30.4 (1997): 80-131. Print.